Armando was a hard man to forget. Slender and slightly wobbly on his feet, he always seemed to wear a look that made you think he was perpetually grumpy. But Sardinia was a land of surprises for me in the 80s, and one of them was the way the chef could use his bony arms to flip the mussels in a sauté pan the diameter of a sewer cover so that they’d head for the ceiling, leaving a soupy tomato vapor trail behind and land—every goddam last one of them—in the pan without a drip to clean up.

These were the heady days when I discovered what Italy and Sardinia were about. You needed to negotiate with the wait staff pleasantly. You could just walk into the kitchen and talk to the chef if you so desired and were polite enough.

We first walked into Ristorante da Armando after a day in the field mapping archaeological sites. Irene, Armando’s wife, appeared at our table to take our order. I can’t remember what we had, but the food was fresh and lively. It made you notice it. And it wasn’t expensive. And it was obvious Irene was really in charge of the joint.

We began to invite other folks from the project to eat with us. The food seemed to get a bit more expensive when they joined us. Then they’d come on their own, and their bill would be quite—well, astronomical. You see, the bill you got was a scrawl of Irene’s writing you could barely read. At the bottom she’d scrawled a total entirely devoid of reproducible addition. Evidently, if she liked you, you didn’t pay much at all. But if you just walked in and gruffly demanded the mussels, she would scratch away and hand you the bill. That total would stare at you brutally. You’d pay dearly for your lack of grace and charm—and no free digestivo for you, bub.

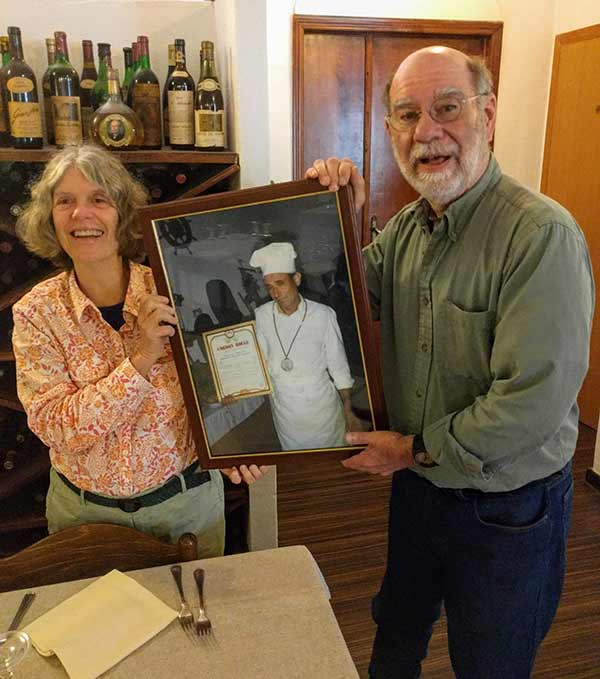

Eventually we learned that Armando had worked on cruise ships, winning culinary awards with some frequency. He was proudest of the one that rewarded him for inventing the dish he called “Agnello in vestiti” which we laughed at, because if your Italian isn’t up to snuff you got a picture of a lamb in a business suit rather than the more appropriate (I think!) dressed lamb. He never told us the recipe, despite our insistence that he make it for us on a special occasion.

Eventually he left the seas and came to inland Sardinia to marry Irene and settle down to the rural life. Legendary is the fact that his special opening was offered to all the residents of Sedilo, and many came. He is said to have kicked them all out, declaring them unfit to eat in a fine restaurant.

Speaking of special occasions, Armando would invite all of his friends to eat at the restaurant on his birthday. Evidently he had lowered his expectations at some point.

One day we went early to the restaurant to see how he prepared for the day. Early every morning he foraged for seafood at the Oristano fish market, about an hour away. When he arrived and opened the trunk of the car, it was as if some fisherman had just shoveled the days catch in there. Of note were the eels, the roasted version being a specialty of the island I never tire of. They were alive and squirming. We tried to imagine what would happen if some miscreant Anguilliformes managed to slither through a rent in the structure and would live and die in an unreachable substructure of the car, a fetid thought indeed.

The restaurant wasn’t in town. It was in the open, next to Nuraghe Talisai, one of Sardinia’s Bronze Age towers. You could stop there and watch the sunset from the top of the tower if you were so inclined, then go to eat on the terrace while gazing longingly at Lake Omodeo below if you didn’t have someone with you who expected to be gazed at longingly instead. The restaurant’s remoteness had that kind of rustic charm you hope for on vacation, but what it lacked was running water. So Armando brought copious quantities of that in his car every day as well. The stick-arms got a brisk workout every day.

So, imagine, if you will, a family restaurant, but a rather large one. By family restaurant I mean it was a place where only the family worked—Armando in the kitchen, Irene in the front of the house, son Roberto grilling the fish out on the terrace when he wasn’t out gallivanting, and Irene’s mother, a woman just over 4 feet tall dressed in black who washed the giant stack of dishes Irene was constantly bringing into the kitchen.

Roberto was the bad boy. His parents worried. His father couldn’t wait until he had to do his obligatory service in the armed forces. It would set him right.

Then, news came to us that Armando had died. The next time we drove past Sedilo I glanced at the sign. It read, “I quattro assi” or The Four Aces. We were sad. It wasn’t the same, but we gambled and tried it. It didn’t suck, but it didn’t stand out either.

Then, while planning a route for our recent trip to the island with our friends Walter and Sharon Sanders, I noticed the marker on the Google map indicating “Ristorante da Armando.” You could have pushed me over with a roasted eel.

The chances that Armando had risen from the dead were, I realized, pretty much zilch. So what does one do? You go there and order the eels.

You interact with the waitress to get eels and other cool stuff like batter fried shrimp and basil leaves. You ask who is running the restaurant. The answer comes back: The Bad Boy.

So after we settled the bill and were brought some after-meal drinks on the house Roberto, all growed up, stepped out from the kitchen and strode to our table to reminisce. We determine it he was 16 or 17 when we saw him grilling the fish. I mention that we’d eaten at The Four Aces, and that seemed like the end of an era for us.

He leaned in, spreading his hands flat on the table and explained, “I spent 6 years at school in hospitality, then came back and reopened the restaurant.”

After a bit more reminiscing, Roberto invited us onto the terrace and plied us with more liquor. We took a picture. Appropriately, Roberto wore black.

Armando would have been so proud. Maybe we’d have to remember the grouch beaming with joy…